Shannon: Queer Times in My Dollhouse

As a kid, my room overflowed with dolls. I had precious porcelain dolls up on shelves, soft rag dolls with yarn hair, a small collection of beloved American Girl dolls with their assortment of tiny accessories, a tangle of Barbies with hand-me-down clothes from an older cousin, and enough Playmobil figures to stock a full model ranch built with my brother. Play, and dressing, and honestly simply having and caring for dolls was a major part of my childhood.

A ‘90s bedroom with two preteen girls on the bed playing with dolls

Please enjoy this glimpse into the mid-90s explosion of my bedroom, where my bff and I play dolls and crimp our hair.

This abundance was granted by my middle-class status but also because dolls were an interest my sister and I both shared with our mom, who collects vintage and antique dolls. She tells of the devastation of finding out some of her childhood dolls had been given away during one of many parental clear-outs: that wouldn’t happen to us, her children, she vowed. So, dolls filled up our childhood play.

Looking back on how I played with them has led me to think more about the gendered quality of dolls being my attachment, rather than blocks or Legos or model cars, each of which share the qualities of tininess and creative building. While I remember playing caretaker for baby dolls, they made way for Barbies, and, ultimately, American Girl dolls soon enough. In American Girl dolls I did feel a deeply gendered attachment. It’s right there in the name: these dolls suggested to me not ways I might end up being an adult – a buxom doctor/president/dog walker/bride like Barbie, a mom tending flopping-bodied baby doll infants – but ways I could be as the girl-child I already was.

A young white girl staring intently at a carousel snow globe

The American Girl dolls in their stories were nerdy, they loved horses, they played tea parties. They were scared sometimes and brave sometimes. They negotiated deeply adult topics, but without the same weight of responsibility the adults in their lives held. They were like me. The grown-up playacting seemingly offered by other kinds of dolls started to have less appeal. Looking back, I can see that the adult lives offered by those toys excluded me, a weird and independent, neurodivergent and deeply queer child.

I pored over the American Girl catalogs, entranced by the clothes, finding in the historical details, richly textured fabrics, and outfit building the same satisfaction that I now find in sewing. I continued to love them “too long,” still asking for American Girl birthday presents well into my teens, a queer way of refusing to grow up.

Two young girls wearing fancy dresses. A doll lies on the floor.

My American Girl Doll of Today, whom I named Marianne, went with me everywhere, including to the oh-so-fancy yearly tea party my mom and I, and later my sister, went to each year. A shiny damask dress for me and a hoopskirt for Marianne felt the height of fashion.

Queer Time

Over the past two decades, queer scholars in the humanities have written a lot on the concept of queer time. In 2005, queer theorist Jack Halberstam wrote that queer subcultures create concepts of time that “[allow] their participants to believe that their futures can be imagined according to logics that lie outside of those paradigmatic markers of life experience – namely, birth, marriage, reproduction, and death,” in his book, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (2). That is, if a cisgender, heterosexual notion of time imagines life as a series of “normal” events that occur at “normal” times, such as being born into a stable gender identity, having your first crushes and undergoing puberty in your teens, getting married and having children, growing old within a nuclear family, and dying at an advanced age, then queerness – by choice and necessity – does things differently.

This is not to say that each and every individual queer life must reject this normative progression, or that the only way of being queer is to eschew straight time. Instead, recognizing queer time helps us understand the damage done when one way of being, one narrative progression of life, is culturally reinforced as natural, normal, expected, and healthier than any other.

A toddler and a young girl from the back, wearing frilly dresses and straw hats.

We’ve been thinking about the queer “inner child” here on SewQueer because of the ways queer childhoods are often disrupted or disallowed. How many of us were not allowed to make sense of our own queer interests and desires as children because we lacked representation, education, and affirmation? How many of us lived a gendered childhood that feels quite alien to the way we understand our genders now?

Recognizing and affirming queer time can allow us to rectify those disruptions and disavowals. It can also offer us new ways to think about our futures. In his polemic 2004 book, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Lee Edelman argues that our contemporary social and political order centers around the figure of The Child – not a specific kid, but an amorphous idea of the children who are our reason for, well, everything. The Child is the one for whom we seek to protect the planet; the Child is the one put at risk from a bevvy of adult decisions from vaccination status to abortion to gun control; the Child is the innocent who must be protected from danger and perversion.

Edelman writes that the image of the Child “serves to regulate political discourse – to prescribe what will count as political discourse – by compelling such discourse to accede in advance to the reality of a collective future whose figurative status we are never permitted to acknowledge or address” (11). That is, this concept of the Child and the Child’s Future has such a stronghold on political discourse that we are rarely permitted to speak wholly for the benefit of adults, here, in the present. We are rarely allowed to acknowledge that the Child’s Future of which we speak is not only figurative – a concept, not a reality – but is also deeply in opposition to the things we actually do for and to children today. Focusing on the mythical future child, at risk of all kinds of innocence-crushing experiences, directs our attention away from both actual living children and actual living adults.

Queerness is often defined and regulated, in the public sphere, around this image of the Child. It is illegitimate because queer relationships cannot produce children; it is perverse and must be shielded from children; it is an adult identity that no child can understand or have themselves. It even shows up in internal queer community discourse, such as debates around the centering of kink at Pride.

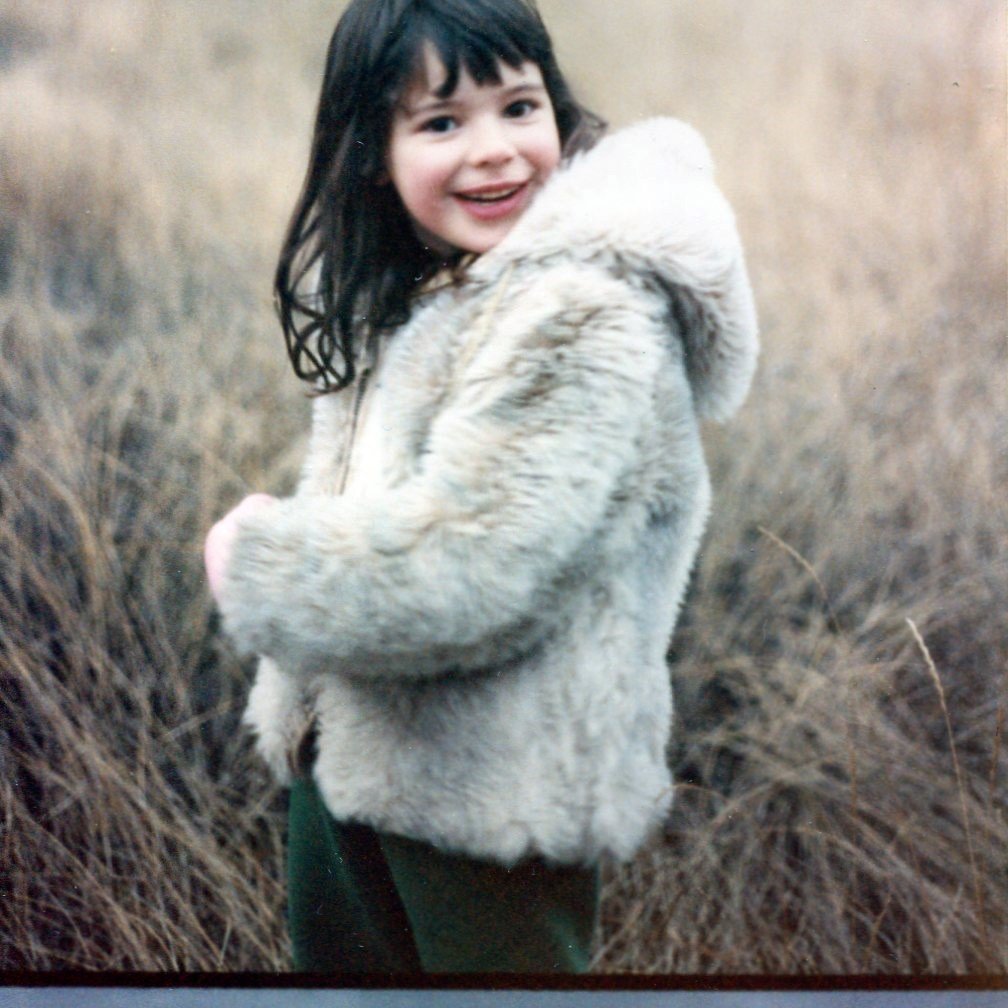

A girl grinning at the camera, wearing sweatpants and a furry hooded jacket

There is no heterosexual explanation for the glee this kid got out of being DRAMATIC.

A Dollhouse For Now

I don’t want kids, and I won’t be having them. I have children in my life: the child of my partner, whom I love deeply, a flock of niblings who are excellent recipients of small handmade clothes, my undergraduate students who are emerging from their own childhoods. None of these children are a central focal point of my life, though.

Thus, in mainstream thinking, my abundant collection of dolls is now unmoored. Because I, as an adult, do not have progeny, there is no lineage to whom I will pass the dolls down. When it comes to their old but beloved childhood toys, most adults see them as valuable in only two ways: to pass down to their children, or to sell.

A shelf of dolls and doll accessories, including a horse, vespa, and loom.

I’m doing neither. This summer I reclaimed my dolls for me, and me alone. I bought and started a dollhouse kit, a dream I’d had for decades. I visited my parents and packed up my American Girl doll gear, my chubby-cheeked Madame Alexander dolls, and my Madeline dolls (if perpetual boys get Peter Pan, then surely girls get Madeline). They live on their own set of shelves in a room of my house that serves all kinds of purposes: doll storage, my office, SewQueer merchandise HQ, and now, my dollhouse workroom.

Workspace with a dollhouse on a table and set of shelves with tools

I started sanding, painting, and building my two-story dollhouse cottage in my living room, and realized I needed a dedicated space. A shelf and a basic Ikea table later, and I have a growing workroom for this tiny hobby that nonetheless takes up lots of space.

Interior of a dollhouse with wallpaper and an unpainted fireplace.

My dollhouse, Pansy Cottage, isn’t for a fantasy of the nuclear family. It’s an Edwardian snug, dedicated to a vision of a turn-of-the-century lesbian spinster activist. She papers the town with suffrage posters and subscribes to all the socialist magazines. She has walls covered in William Morris wallpaper and a little natural history collection. She has a bed that is hers alone, occasionally shared with a like-minded lover.

Miniature historical magazines and posters dedicated to women’s suffrage and socialist causes.

She’s the vision of adulthood no dolls ever offered to little baby dyke me. She lives the imaginary historical version of my life, in the miniature alternate reality house of my dreams. I work on her house in the workroom I built instead of a guest room, instead of a nursery, instead of a dining room, instead of the spaces I am “supposed” to have in my house. The queer, spinster, academic, creative life I live is perfect for me, and my timelines are joyfully unaligned with straight time.

While reclaiming my childhood dolls honors and nurtures my inner child by reconnecting to these joyful tiny objects just for me, without the presumption of passing them down, my dollhouse project is less about affiliation with that inner child. Instead, it helps me in declaring the queer adulthood I desire – the adulthood I am shaping for myself.

It’s an adulthood centered around play, creativity, joy. It’s an adulthood in which I think through and connect to my identity, my past, our queer histories through reading, writing, and making. Rejecting straight time takes getting our hands dirty. It takes work, creativity, imagination, and a driving urge to form community beyond the straight-time logic of the nuclear family. Queer cultural critic José Esteban Muñoz calls this ecstatic time, ways of being that are marked by desire and ecstasy, by happiness and contemplation, by looking towards communal futures that are better for us, not just mythical future children.

It’s with desire, ecstasy, joy that I make my dollhouse, that I make my life, that I make my relationships. It’s queer time that I live in, queer attachments that I hold dear, and queer creativity that nurtures my queer self.

Want to read more about queer time?

“Queer Temporalities” issue of GLQ, vol. 13, no. 2–3 (2007).

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Freeman, Elizabeth. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

Halberstam, Jack. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York: New York University Press, 2005.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. Sexual Cultures 13. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

Stockton, Kathryn Bond. The Queer Child, or Growing Sideways in the Twentieth Century. Durham: Duke University Press, 2009.

Shannon (she/her) is a queer sewist and art historian, living and teaching in the midwest. She shares her own sewing, mushroom farming, and dollhouse making on Instagram at @rare.device and is the founder of SewQueer.

Sew Queer is a community, and we welcome comments and discussion. In order to create a welcoming and multivocal space working towards a more just and equitable future, we review every comment before approval. Comments promoting racism, classism, fatphobia, ableism, or right wing political ideology are not allowed and will not be approved. For more details on commenting, visit our commenting guidelines.